Under the Erie Railroad

The Winsor Street Overpass (1890), the city's oldest railroad overpass, was built nearly 25 years before a systematic effort was undertaken to separate train traffic from the streets of Jamestown. A simple plate girder bridge with rusticated limestone block retaining walls, the bridge was built to support two tracks.

A westward view beneath the bridge, showing steel supports with bracing plates and heavily corroded surfaces.

A close-up view of the bridge's plate girder support system. When the bridge was built, Jamestown had 16,000 residents and the area around Winsor and Harrison was one of the city's busiest industrial hubs. The overpass eased transit between factories there and the rapidly expanding residential districts along the East Second Street corridor.

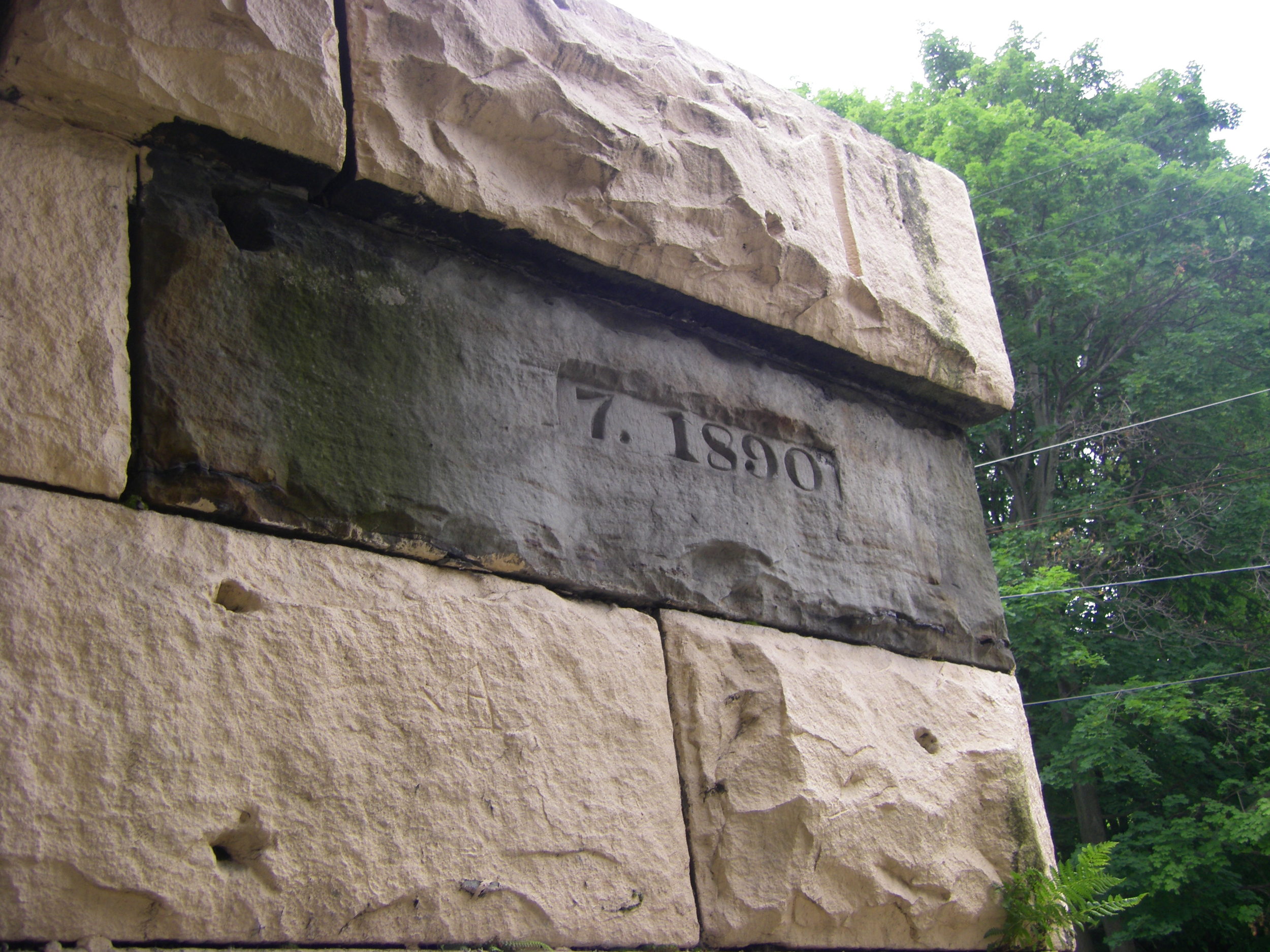

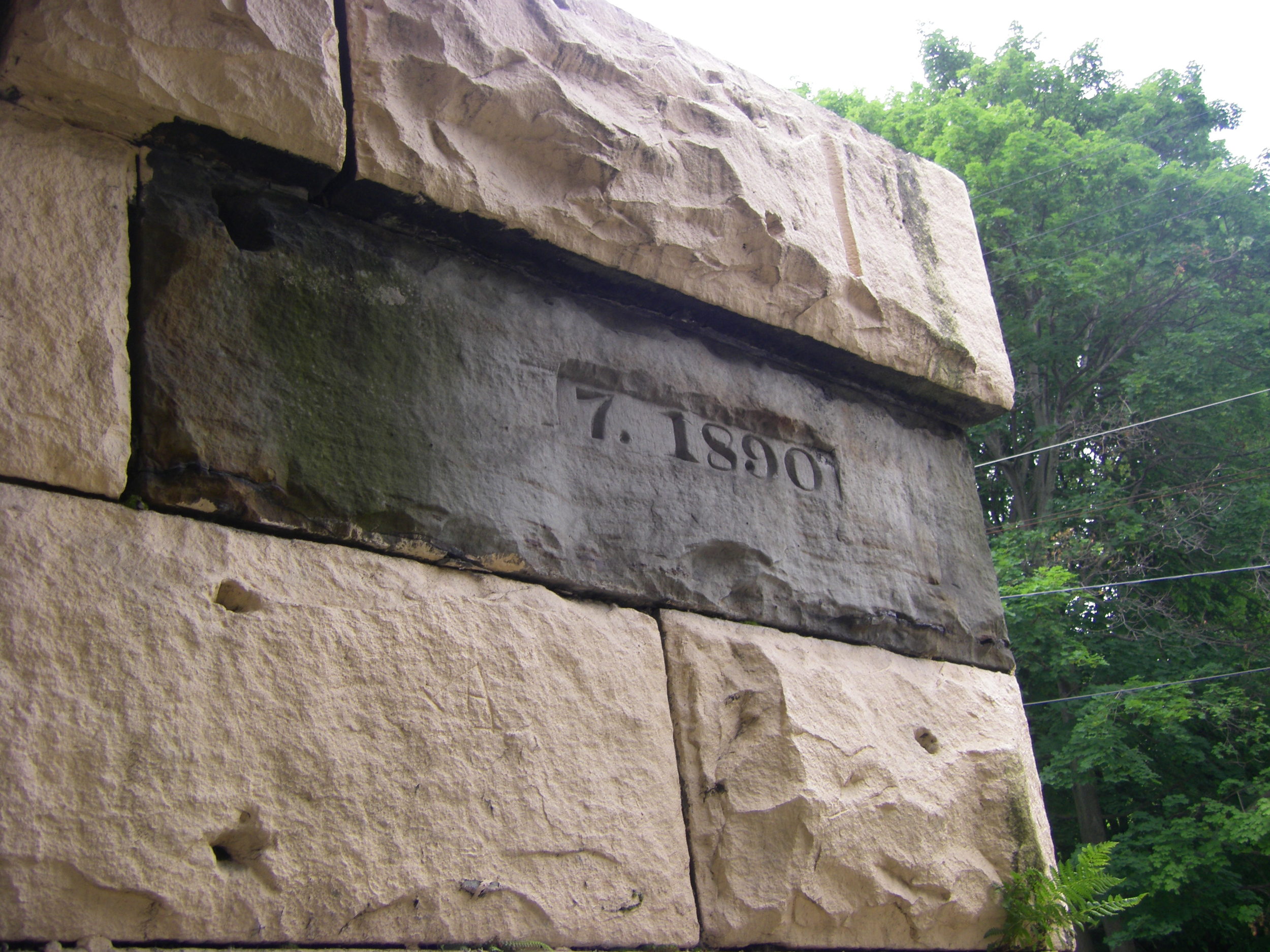

This stone block on the bridge's northwest corner includes the bridge's construction date. The surrounding blocks on the retaining wall were painted within the past five years in an attempt to cover graffiti.

The track level of the Winsor Street Bridge (looking east from Chandler Street) shows the bridge's two-track capacity. Only one track remains in service.

Stepped profile of the bridge's retaining wall.

The railroad bridges over the short, winding segment of West Second Street (just before it crosses the Chadakoin) was the first component of the joint effort by the Erie Railroad, the City of Jamestown, and New York State Public Service Commission to remove almost all of the city's at-grade crossings. It was completed in 1916.

This view, looking north, shows the two spans (both with capacity for two tracks) that comprise the overpass.

Northward view in between the two double-tracked spans, both of which are simple plate girder bridges. Unlike the overpasses completed later over Main, Foote, and Buffalo, this overpass lacks rows of columns to separate pedestrians from street traffic.

The reinforced concrete retaining wall that lines the overpass is showing its age, with significant surface chipping.

The overpass's eleven foot spans supported four sets of tracks in an area between the Erie Railroad's 1931 passenger depot, a maintenance facility, and a once-busy rail yard.

The eastern retaining wall of the overpass contains a plaque noting the year of the overpass's completion and the construction firm that performed the work. The local firm Mahoney & Swanson was hired to complete a full system of overpasses in 1912 but only got this far due to poor project management. Following World War I, the McMullen Company of New York City was hired to complete the remainder of the Erie's overpass system in Jamestown.

The busiest at-grade crossing in the city was at Main Street, where traffic (including busy streetcar lines) crossed the railroad tracks and the river that separated downtown from Brooklyn Square. The Main Street Overpass was completed in 1926 after nearly two years of work to elevate the tracks through downtown.

The tracks through downtown were elevated through the construction of reinforced concrete trestles and retaining walls. This view of the viaduct's south wall, east of the Main Street Overpass, shows gaps that were either filled with gravel or left open to serve as coal storage for adjoining factories.

The Main Street Overpass is a steel girder bridge that was then sculpted with with an outer shell of reinforced concrete. This view beneath the overpass shows three rows of arches on the west side of Main Street.

Soon after the overpass was completed in 1926, spaces beneath the structure were walled-in to create leased commercial space -- a unique feature for any railroad beyond the East Coast. The spaces were occupied for decades by retail tenants but were demolished between 2010 and 2012 after sitting abandoned and derelict.

The Main Street Overpass identifies the railroad and the two terminals that served the route through Jamestown -- Chicago and New York. The letters on the overpass are all filled with mosaic tiles.

The space on the overpass long served as a source of advertising revenue for the railroad (just as the storefronts under the bridge served as rental revenue). The overpass was covered by by advertising for decades -- including ads for Jamestown's First National Bank and later McDonald's. The original concrete and mosaic tile surface was restored in the early 2000s.

View of the Main Street Overpass from across the Chadakoin River. Demand for space at the center of town was once so strong that, in addition to storefront spaces beneath the overpass, buildings were constructed over the river (including at the South Main Street Bridge), largely obscuring views of the river until urban renewal cleared most of Brooklyn Square in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

When the railroads were elevated through downtown, Institute Street (formerly a through-street from Harrison to E. Second) was closed to traffic. But due to heavy pedestrian traffic generated by the high school and factories on both sides of the railroad, the decision was made to build a pedestrian subway under the railroad. It was completed in 1925.

The subway was operational until the 1990s, when deteriorating conditions and concern for the safety of high school students who used the subway led to its closure. It is currently sealed and covered by overgrowth.

The entrance on the north side of the railroad, directly behind Jamestown High School -- also sealed and covered with overgrowth.

Completed the same year as the Main Street Overpass (1926), the Foote Avenue Overpass is a simple plate and girder bridge with capacity to carry four tracks.

The reinforced concrete abutments and retaining walls include simple but graceful arched passageways for pedestrians. This view of the northeast corner of the overpass shows the date of construction.

The reinforced concrete columns and arches beneath the overpass show signs of corrosion, as do most elements of the century-old system of grade-separating infrastructure. With the decline of railroads after World War II, and the mergers and bankruptcy's of the 1960s and 1970s (leading to Conrail's takeover of this line, which is now owned by Norfolk Southern with a short-line operator), deferred maintenance on these privately-owned assets is considerable.

Full view of the pedestrian passageway on the east side of the overpass.

Shadows, light, and rows of arches make the pedestrian passageways dramatic spaces to pass through.

The last phase of the grade-separation project that commenced in 1912 and finished in 1927 was the Buffalo Street Overpass, a three-track overpass that crosses the street at a sharp angle.

As with the Main Street and Foote Avenue overpasses, this one has single rows of reinforced concrete columns that shield pedestrian traffic from the roadway -- also these arches are blockier and wider than the others.

The reinforced concrete retaining wall of the overpass showing the 1927 completion date.

View of the underside of the track deck. Steel I-beams resting on the concrete retaining walls span the roadway with rivets attaching them to smaller, rib-like cross-members.

Although a narrower span than the overpasses on Main Street and Foote Avenue, the pedestrian passageways are longer (and more intimidating, especially at night) due to the overpass's crossing angle.

The completion of the grade-separation project in 1927 coincided with a separate project that also made it easier to travel within the city -- the Third Street Bridge. Prior to the bridge, the quickest way to reach the Westside from downtown was via the Fairmount Avenue Bridge. After crossing the river, traffic had to wait in line at Fairmount's busy at-grade crossing. Due to the site's topography, an overpass there was impossible.

That crossing was finally closed with the opening of the Sixth Street Bridge in 1937. But pedestrian traffic generated by the factories along Jones & Gifford Avenue necessitated a safe pedestrian crossing, resulting in the Fairmount Avenue Pedestrian Subway.

The date of construction, stamped onto the entrance of the portal on the east side of the tracks.

This peculiar vestige of the Industrial Age is still open to pedestrian traffic, although garbage, graffiti, and low light prompt most crossing at this location to simply walk over the tracks.

A view of the portal on the west side of the tracks, with warehouses of the old Art Metal Company beside the tracks to the right.

West of the tracks, a rather densely populated area retains many of its characteristics from the time of the subway's completion, including low-rate rental housing and a neighborhood firehouse.

One hundred years ago, Jamestown had a big traffic problem on its hands. Over 50 trains passed through the bustling city of 40,000 on a daily basis -- trains that utilized 13 separate at-grade crossings where they competed with a growing number of cars, trucks, pedestrians, and a busy streetcar system. The railroad's east-west route through the middle of the city -- paralleling the course of the Chadakoin River -- meant that almost anyone who traveled between the north and south sides of the city had to wait patiently for tracks to clear and traffic to flow.

The inconvenience and danger that the busy at-grade crossings posed to city residents, as well as the liabilities they posed to the Erie Railroad, brought about a project to separate train traffic from other city traffic through a system of bridges and tunnels. The effort was launched in 1912, with costs divided between the railroad (50%), the city (25%), and the New York State Public Service Commission (25%). However, due to incompetent contractors and World War I, much of the work didn't begin until the mid 1920s. The project finished in 1927, with one additional project (the Fairmount Avenue Pedestrian Subway) added in 1936 to coincide with the construction of the Sixth Street Bridge.

This annotated gallery provides a glimpse of the bridges and tunnels that provide almost complete grade separation for the Erie Railroad in Jamestown. Today, the only streets within the city limits where vehicles must cross an active railroad track are Tiffany Avenue and Lister Street.

Published on by Peter Lombardi.